Haere Hau Pa

Haere Hau Pa

TRACES STILL TO BE SEEN OF WHAKAAHU-RANGI HIGHWAY OF MAORIDOM

Only from a plane are there still discernible, to a keen-eyed airman, traces of that great highway of Maoridom, the Whakaahu-rangi Track, on which many of the great figures of history came and went in the centuries before the pakeha. The track, paralleling, fairly closely the present road between Lepperton and Patea, was part of the line of communication between Kawhia and Wellington. It avoided the country of the Taranaki tribes and was the means of uniting, by marriage, the leading families of the tribes descended from the people of the Aotea and Tainui canoes at Patea and Kawhia respectively. The trail was the major route from north to South Taranaki for many hundreds of years. The name is derived from a journey made by a Maori woman; Ruaputahanga, as she made her way back to her people in south Taranaki from Kawhia. Near present Stratford she slept looking up at the sky and the trail received it's name - Whakaahu-rangi or "turned towards the sky."

Ruaputahanga, the maiden of Lake Potakataka

The romance of this union lies in the story of Ruaputahanga, a maiden of renowned beauty, daughter of Keru, 7th generation in direct line from Turi, who lived at Paranui Village, east of Patea, and whose fame had reached the ears of Turongo, son of Tawhao chief of Kawhia. Turongo came to Patea but his wooing of the Aotea girl met with little success. Rua was in the habit of bathing in a lake called Potakataka, between Patea and Whenukura near the sea, and here Turongo went, hiding in the scrub by the water‘s edge, until Rua came to bathe.

He watched her disrobe and enter the water and then slipped up and picked up her clothes. Rua, endeavouring to hide herself in the water, asked Turongo what he wanted. His reply was that she should be his wife.

Rua could see no way out of the compromising situation and agreed. The story goes that she said: “It is well. Return to your home and your people, and in due time I and my people will come. Indeed, you have seen me in all my nakedness and I must perforce become your wife." So Rua went to Kawhia — but did not marry Turongo. It was in the end Turongo’s half-brother Whatihua who, captivated by her beauty, persuaded her to break her promise to Turongo and to become his (Whatihua’s) second wife. Turongo eventually married Mahinarangi, descendant of Kupe, the navigator and Paikea, captain of the Horouta canoe and from them sprang a line of illustrious chieftains beginning with their son Raukawa and ending with the five kings of Waikato, Potatau, Tawhiao, Mahuta, Te Rata and King Koroki

Rua bore Whatihua two sons but her husband’s first wife did not agree and eventually she left Kawhia, although Whatihua pursued her down the coast, beseeching her to stay. At length, weary of body and sick of heart, she arrived at at Mokau, where she stayed for some time, later becoming the wife of Mokau, the man after whom the river is named. For some reason not recorded except that she tired of Mokau, she left Mokau, and turned for her old home in South Taranaki, taking an old war trail which led to the east of Mount Taranaki. At a place near where Stratford is built she camped for the night. In going to sleep she lay on her back with her face up to the clear sky, and hence the name of that place and the track itself Whakaahurangi (Whaka-ahu to turn upwards; rangi, the heavens). Rua eventually reached her own people, one version saying she died at Orangituapeka Pa near Manaia. All versions agree, however, that she married again this time to Porou.

Waitore

Very close to Ruaputahanga's bathing pond; Potakataka on the Whenuakura coast is another significant site called Waitore. Over the years significant wooden artifacts from canoes have been found in this swamp area, they are currently in Aotea Utanganui and Puke Ariki Museum's.

Rangitawhi

At the mouth of the Patea River on the eastern side was Rangitawhi, the Pa built by Turi and his followers when they arrive in Patea in the 1300's. No trace of it can now be seen, as it has all eroded away with sand drifts. A substantial wharenui called 'Paeahua' was a feature at Rangitawhi. In his book 'The Story of Aotea', Rev TG Hammond tells of the remains of the Tuahu/Altar named 'Ranitaka' still on the landscape in the early 1900's... 'large slab-like stones from the bank of the river'. The village built nearby was called Kurawhao and was situated near the old Patea Railway station. Their cultivation's were on the site of the Harbour Masters house on the hilltop above and was called Hekehekeipapa. The stream 'Pararakiteuru' runs out of a spring above the railway cutting into the swamp below.

Tihoi

Tihoi was a fortified Pa on the Cliff overlooking the Whenuakura River mouth from the Patea side. It is thought it was built by Keru; a grandson or great grandson of Turi. When EJ Wakefield walked through in 1840 he described it as having a double row of palisading with the space between filled with earth, leaving small holes level with the ground through which muskets could be fired from a trench behind. It seems probable that Te Rauparaha modified the Pa for musket warfare in about 1823, when he spent some time there training his men for his expedition to the South Island. Te Oho, adjacent to Tihoi, was a fishing village associated with the Pa. The Papakainga associated with the Pa was called Paranui, situated near Baker's woolshed on Rakaupiko Road.

Haere Hau Pa

Haere Hau Pa was a fortified cliff top Pa on the south side of the Patea River, upriver a few hundred metres from the sea walls. EJ Wakefield also stayed here when he walked through in 1840. It was near the site of Wai-o-turi Marae. Haere Hau urupa overlooks the town of Patea, on the cliff top behind Wai o turi.

There was also a papakainga on the site of the town oxidization ponds between the Bridge and the River mouth. This area was later the site of the first European settlement in the 1860's, before the town moved up to its current site.

Wai-o-turi Pa

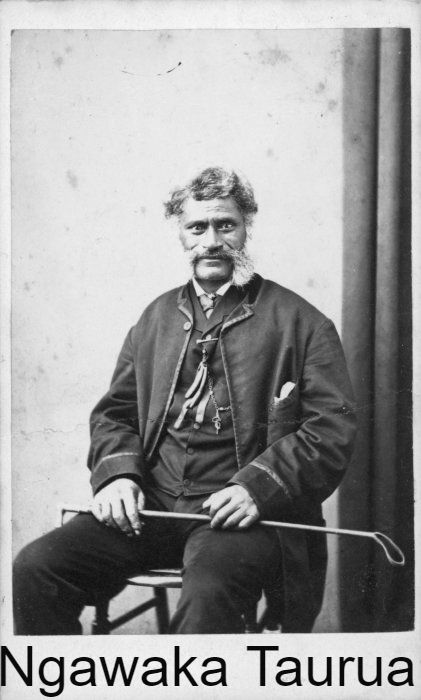

Wai-o-turi is on the south side of the Patea River, near the site of Haere Hau Pa. During the land Wars of the 1860's the area was part of the mass land confiscations by the Government. Upon his return from imprisonment in Dunedin with Māori Prisoners, in 1872, Chief Ngawaka Taurua fought long and hard to have this sacred place returned to his people. In 1876 Wai-o-turi was allocated back to Taurua and his people and was legally dated on the Crown Map in 1882 in his name. But it wasn't until 1933 that a new meeting house 'Ko Matangirei' and other buildings were built, and a large settlement established.

Kakaramea Redoubt

The Colonial Kakaramea (or Cameron) Redoubt on Wilson Road, was built on an existing fortified Pa, probably called 'Kakaramea Pa'. Further south near McKenna Rd was a kainga called Te Awhi. These were destroyed after the battle of Te Ngaio on 13 March 1865. Private James Nixon was the only european soldier killed in the battle, he was buried at the Kakaramea Redoubt, then re-interred on the hill at Scotland Street cemetery, Patea. The 50-80 Maori killed in the battle may also be buried in the vicinity.

Battle of Te Ngaio

Te Ngaio is the area of land between Whitehead Lane, Patea and the village of Kakaramea.

General Cameron had marched in his deliberate way up the coast and had established posts at several places as far as the Waingongoro River. The principal opposition he encountered was at Te Ngaio, in the open country between Patea and Kakaramea. The General, with about a thousand men of all arms, moved out from Patea camp on the 13th March for the Waingongoro. At about two miles from Patea volleys were fired into the column by a body of Māori’s posted under cover of a ridge parallel to the line of march, on the right, near the Patea River. The advance-guard was thrown out in skirmishing order, bringing round the left flank to attack the natives. The Hauhaus fell back in good order towards Kakaramea, fighting well in the open, with deliberation and bravery. There were about two hundred natives in action, and for all their inadequate numbers and inferior arms they opposed a manful front to the invading army. Retiring along the swampy ground toward Kakaramea they made the most of their knowledge of the terrain and their native genius in skirmishing, but nearly half of them were shot down. Eighty natives were killed (also reported that it was nearer to 50). It was the heaviest blow in point of causualties that the Hauhau tribes suffered in the West Coast War.

Tu-Patea, of Taumaha, describing this engagement of Te Ngaio, which was fought over his own tribal lands, said:— “I followed my elders into action, armed with my tomahawk. Over two hundred of our people came out to fight in the open. There were five women among them, not armed, but urging the warriors on. One of them, Tutaki's wife, was killed. The principal chiefs were Patohe, my father Hau-Matao, Te Waka-taparuru Paraone Tutere, and Te Mahuki. Our prophet was the old man Huriwaka, from Otoia, on the Patea. His god was Rura. Huriwaka, before the fight began that morning, prophesied saying, ‘To-day's battle will be good; it will be a favourable fight for us.’ But we were beaten, and eighty of our people fell on the field of Te Ngaio.”

There were many instances of native heroism and daring. An eye-witness, Dr. Grace, surgeon in the force, wrote: “The dignified and martial bearing of the Māori touched the hearts of our soldiers.” In the field hospital afterwards General Cameron asked a badly wounded warrior, “Why did you resist our advance? Could you not see we were in overwhelming force?” The Māori replied, “What would you have us do? This is our village; these are our plantations. Men are not fit to live if they are not brave enough to defend their own homes.”*

The tribes engaged in the fighting at Te Ngaio were chiefly Ngati-Hine, Pakakohi, and Ngati-Ruanui. It was the final attempt in strength to dispute the right of way with General Cameron. “The soldiers,” wrote Dr. Morgan S Grace in his “Sketch of the New Zealand War,” “no longer desired to kill the Māori, and disliked more than ever being killed by him.” He heard the sympathetic Irish soldiers say, after the exhibition of native bravery at Kakaramea (Te Ngaio):

“Begorra, it's a murder to shoot them. Sure they are our own people, with their potatoes and fish, and children. Who knows but they are Irishmen, with faces a little darkened by the sun, who escaped during the persecutions of Cromwell!”

Dr. Grace was in error, however, in a statement that very few of the Māori’s were killed in this battle in the flax and toetoe. The report of Colonel T.R. Mould, R.E., giving twenty-three as the number killed and mortally wounded, was equally astray. Wells's “History of Taranaki” makes the loss thirty-three killed, left on the field. A list of casualties in Gudgeon's work gives the killed at fifty-six—also under the mark. It was natural that the Maori losses should have been underestimated in the official reports of this and other engagements, as most of the dead were usually carried off the field. It is clear now from the narratives given me by Tu-Patea and other natives that the Hauhaus lost eighty killed at Te Ngaio, besides having many wounded.

A veteran transport bullock-driver who witnessed the encounter at Te Ngaio says: “After the battle I saw the dead body of the biggest Maori I ever set eyes on—he must have been 7 feet high.”

British casualties were a private of the 57th Pte James Nixon, shot dead and three men wounded. That afternoon the British force encamped in the captured village of Kakaramea, where a redoubt for 150 men was at once commenced. The position was about six miles from the coast and close to the Patea River; the present Township of Kakaramea is more inland and on higher ground.

On the following day the column moved on and camped at the Maori village Manutahi, three miles from the historic village of Manawapou, on the sea-coast. Detachments were sent to Manawapou, which was on the left bank of the Ingahape River, at the mouth; and, as it seemed practicable to beach boats on the sandy shore on the opposite side of the river, redoubts were constructed on the high ground to cover a depot of stores.

Otoia Pa

Pre 1869 the Otoia area of the Patea River was heavily populated by Te Pakakohi Maori. They had eel-weirs built across the River and abundant vegetable plantations on the riverflats. Owhio Gorge is the larger Gorge next to Otoia, and the Owhio Stream runs through it and into the Patea River. There were several different iwi living in neighbouring Papakainga/Village's - Whakapaiho Pa, Ruatuna Pa, Te Ngana Pa, Otoia Pa, Otautu Pa and Tupopou Pa.

Manutahi Pa

Also known as Te Takere o Aotea Marae on Taumaha Road was the prominant Marae in the area after Manawapou Pa was invaded and burnt by General Chute in the mid 1860's. Te Aotawhi Church was built on the Marae in 1886, one of three built after their men returned from imprisonment in Dunedin, the other two were at Hukatere Pa (Whenuakura) and Tauranga-ika (Nukumaru) known as Tutahi Church - a sacred stopping point still today. Te Aotawhi Church at Taumaha was dismantled at some stage and parts of it taken to Ratana to be used for a church there. The Church at Taumaha now is not the original.

Another papakaianga in the Manutahi area is Kaihuahua Pa, it was situation north of Manutahi, on the inland side of the main road, just before the Manawapou Hill.

The original Manutahi Pa was located on the hill top to the north of Taumaha Road where the rail way line intersects the road. It was a fortified native village within a circular stockade, which consisted of huge posts sunk in the ground and projecting upwards to a height of about 12 feet. In this enclosure were the whare and storehouses and a wharepuni named Parekau. Entrance to the pa was by the way of four separate gates, situated at points north, south, east and west of the stockade at each gate was quartered a certain tribe

The impressive Manawapou Pa was along the coastline overlooking the sea. This large fortified Maori village on the cliff top on the left bank of the Manawapou River had a commanding view of the area. Until the mid 1860's it was the home of a section of the Ngati-Ruanui, notable for the large stature of its men.

Turangarere is a sacred hill on the sea side of the main road at Ball Road intersection. It was a meeting place of early Maori, near the Mangaroa Stream. It is thought that the daughter of Chief Wharematangi is buried on top of the Hill.

Maori Land League hui ; early in 1854 at Manawapou

The formation of the Maori Land League, at a great hui of the West Coast tribes, at Manawapou, occured in the autumn of 1854 to discuss and oppose the sale of Taranaki lands to European settlers. Manawapou Pa was on the cliff top overlooking the sea, on the south side of the mouth of the Ingahape (Manawapou) River. An unusually large Wharenui was built for the gathering; it was 120 feet long and 35 feet wide. “Taiporohenui,” was the name given to it. This hui of the tribe agreed that no more land should be sold to the Europeans without the general consent of the federation, and that Maori disputes should not be submitted to European jurisdiction but should be settled by tribal runanga (councils). The idea of a Maori king for the Maori people was also discussed and fervently approved. Titokowaru was among those who signed the great oath, in his address to the crowd of over 1000 people he said…'the man first; the land afterward'. ….'My mother is dead but I was nourished by her milk. Let our land be kept by us as milk for our children'.

Kuranui Pa

Situated on an elevated, sharp bend in the Patea River between McColl's Bridge and the Dam. The Kuranui Stream runs into the Patea River nearby. Kuranui is another name for Moa and it is thought this was a Pa used for hunting Moa and not lived on in a permanent basis. It was the place that Ngawaka Taurua and his people sought refuge in from the Colonial forces in 1869. On the 13th June 1869 Ngawaka and other Te Pakakohi people were captured at this Pa. "In June Major Noake made a canoe expedition up the Patea, taking two hundred and seventy men in his flotilla, and captured the old chief Ngawaka Taurua and many of his Pakakohi Tribe. The warriors surrendered their arms, and were taken out to Patea. Gradually other sections of the tribe were rounded up on the Patea and the Whenuakura, until practically the whole of the fighting-men of the Pakakohi were captured, to the number of over a hundred, besides most of the women and children. The men, to their great disgust, were transported to Otago, and were not released until peace was thoroughly established on the West Coast. Had the Pakakohi anticipated this imprisonment it is extremely unlikely that they would have surrendered as they did". From: (THE NEW ZEALAND WARS: A HISTORY OF THE MAORI CAMPAIGNS AND THE PIONEERING PERIOD: VOLUME II: THE HAUHAU WARS, (1864–72)

The Aotea Waka Monument

Unique among all the memorials erected from one end of New Zealand to the other, a replica of the famous Aotea, or Aotearoa canoe, resting on its six great pillars that parallel the highway at Patea, is an arresting edifice, if not to local residents familiar with it, then most certainly to travellers with time to pause awhile and ponder the simple inscription: “This token of remembrance . . . by the descendants living throughout Aotearoa – of their ancestors Turi and Rongorongo, their family and fellow voyagers." And so the legend of Turi’s coming has to be re-told, as retold it must be to the end of time, for here is a treasured piece of the very history of the place, called Patea, these past six centuries or more. One of the most skilled of the many brilliant navigators who stud Maori folk-lore, Turi abandoned the sea at the end of his greatest voyage in the 14th century migration from Raiatea, one of the Cook Island group, earlier known as Hawaiiki, and walked in search of a “river that flows towards the setting sun.” He came upon Patea, for there the land that Turi smelled — “Te Whenui i hongia e Turi” – was sweet, as he had been told by the explorer, Kupe. “Ka patea tatoru,” which appears as an inscription on the mayoral chain presented to the Borough last year by the family of the late Mr F. Ramsbottom, a former mayor, were the words with which Turi informed his followers that they could lay down their burdens, having reached journey’s end.

Ten figures are represented in the canoe — Turi, his wife Rongorongo and their infant son nestling in a cloak on his mother’s back, Turi’s son Turangaimua and brother Rewa and five other men. In all, 11 hapus were represented among the passengers. On the voyage from Raiatea, Turi’s Party called at the small island Rangahua, supposed to be in the Kermadec group, and there gathered seeds of the karaka.

The Aotea reached New Zealand, land of the long white cloud, about Christmas time and it is generally conceded that it landed near the East Cape “when the lovely pohutukawa was in bloom.” It was a wonderful sight for the men who had been tossed about on the high seas for so many weeks.

In their search for fertile land the wanderers in due course arrived at Waitemata, which had been described to Turi by Kupe. According to legend they hauled their canoe across the isthmus from Tamaki to Manakau and sailed down to the Aotea anchorage at Raglan, where they went ashore to continue their search on foot, a scout, Pungarehu, being sent on ahead of the main party. Turi named several places as they journeyed and, with few exceptions, many have persisted until the present day. Kawhia was the first reached and so named because the party had to journey round the harbour. They travelled on, past Marokopa, Mokau, Waitara, Mangati and Matakitaki to Ngamotu, “where the earth did not smell sweet.” Then to Tapuwae, Oakura, Kaupokonui (the head of Turi), Marae-Kura, Kapuni (the encampment of Turi), Waingongora (the place where Turi snored), Tangahoe, Ohingahape and Whitikau.

Turi gave Mount Taranaki its name. A tribe led by Taikehu was said to be in possession at Patea when Turi arrived and legend has it that the two agreed to settle together, their people intermarrying and become one tribe, their pa being sited on the south side of the river and defended by the natural formation and the headland Rangitawhi. A large meeting house Matangerei was erected in the pa with a whata or storehouse called Paeahua. A nearby spring was named Pararakiteuru and, to make provision for religious ceremonies, an altar was erected and named Rangitaka.

First Kumara Harvest

Chanting some of the old songs, the tribes broke up the soil with wooden spades and planted the few seed kumara they possessed. The actual planting was done by Turi’s wife, Rongorongo, who was skilled in such work and broke the soil very finely. She formed small mounds of the fine soil and planted a seed in each. The mara (cultivation) was named Hekehekeipapa (where the Harbour Masters house is now on Whenuakura side of the River) and the virgin soil was fertile an enormous quantity was harvested. The Karaka seed brought from the Kermadecs was planted on the north bank and evidence of the groves which grew persisted until comparatively recent years; seed from this named Papawhero being carried up and down the coast.

Some of Turi’s people later settled to the north of the river near a good spring at Otaraiti and between two good fishing grounds, Whitikau and Kaitangata.

Another name which persists among the people in the district, Tupatea, arose from an incident when a party, led by Turangaimua, departed for the south. The chieftainess. Taneroa, daughter of Turi, drew attention to the fact and uttered a bitter curse as they stood in the river. Hence Tupatea — standing in the Patea River. According to some authorities, Patea should have been spelt Pa-wa-tea, the pa with a clear outlook. Troubled circumstances, believed to be the death of Turi's son in battle with another tribe, added yet another chapter to the legend of Turi. He disappeared, some claim back to Hawaiiki, and his last resting place remains a mystery. But he left behind him descendants who were to become. a great race of people and who still have descendants living in the region

Raumano

The land behind the site of the Patea railway station is known as Raumano, or the place of a thousand leaves. It was said to have been a swamp producing flax, tutu, raupo and toe toe and was the home of pukeko, parera and Kotuku. An old chant sung by the Maoris of Hukatere told of a landslide in that locality, which carried away many people into the sea “and across to the West Coast.” Pariroa Pa, lying in a sheltered valley off Wilson Road at Kakaramea, replaced Huketere Pa on the eastern bank of the river when Huketere came under tapu. This area and nearby Otoia Pa nearer to Alton is the home of Te Pakakohi Tribe.

DIVISION OF PEOPLE INTO MAIN TRIBES

The people of the Aotea canoe, after their arrival in this country about the year 1350 A.D., made their first home at Patea. It was at Patea that trouble broke out which divided the people into the main tribes of Ngati Ruanui and Nga Rauru. It happened this way; Turi, the leader of the Aotea migration, had a number of children, among whom were a son, Turanga-i-mua, and a daughter, Tane-roroa. Tane-roroa mar-ried Uenga Puanake, a man of high rank of the Takitimu people. At the instigation of Tane-roroa, her husband killed some dogs belonging to Turanga-i-mua. These they cooked and ate. The story says that at that time Tane-roroa was expecting a child and craved for the flesh of dogs. Turanga-i-mua soon found out about this and the thieves were exposed. Thus Tane-roroa and her husband could no longer remain in the old home so they crossed the river and settled to the north at a place called Whitikau. This is three miles down the coast from the mouth of the river toward Kakaramea.

Founder of Tribe

Whitikau became, in later Years, a famous place in the story of South Taranaki for it was here that Tane-roroa's child Ruanui was born, he who founded the tribe that even today carries his name. Ngati Ruanui’s lands of old stretched from the northern bank of the Patea River almost to Oeo and inland to the slopes of Mount Taranaki. At Whitikau there was a famous place of learning called Kaikapo and it was in Kaikapo that a quarrel broke out which was followed by a further division of the people. Some of Tane-roroa’s tribe left Taranaki after this quarrel and went, it is believed, to Wairarapa. South of the river the people of Turanga-i-mua spread over the country- side, building villages and fortifications, mainly in the coastal strip but also inland in some places. The tribe took the name of Nga Rauru after an ancestor.

Turanga-i-mua was a great warrior and led expeditions to other parts of the country, meeting in battle those members of the earlier migrations who could gather war parties to oppose him. Maori history — that is the stories handed down by the descendants of the last migration — is full of stories of how the original inhabitants fled before the powerful new comers.

Counter attack

However, they must not all have been as ‘unwarlike’ as the stories say because after one battle in which Turanga-i-mua had gained a notable victory, the survivors came back with a counter-attack in which Turanga-i-mua and a number of his leading warriors lost their lives.

The battle took place in the Ruahine Ranges. Turanga-i-mua’s body was brought back to Patea by the survivors and there his aged father Turi mourned for his warrior son and could not be comforted. Turi then disappeared and the story is that his spirit fled from the new home to the old and found peace at last in the islands from which he had set out long years before as the leader of the great adventure. Turi must have been saddened too by the enmity which had arisen between his children. The quarrel which had broken out be-tween Tane-roroa and Turanga-i-mua was not allowed to die down. Over the centuries it simmered, now and again breaking out into open warfare.

Great Leaders of the 1800's

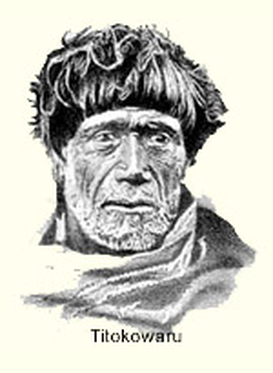

Riwha Titokowaru was undoubtedly one of the most strategic warrior of Land Wars. Despite being heavily outnumbered Tītokowaru won several stunning victories. He was both an extremely talented military engineer and a master of tactics. By early 1869 he had won back 110 km of territory between the Waingongoro and Whanganui rivers. His force grew from 150 to around 1000, and he gained the tacit support of the King Movement. His victories almost brought the colony to its knees, and the government considered returning confiscated land. But at the height of his success Tītokowaru’s army mysteriously fell apart. As Belich remarks, Tītokowaru lost his war but the government can hardly be said to have won it. The government left Tītokowaru alone, and he became a strong supporter of the pacifist prophets Te Whiti and Tohu at Parihaka. When creeping confiscation began again in 1878, he helped to organise a campaign of non-violent resistance.

Ngawaka Taurua was the tribal leader of Pakakohi, based a Hukatere Pa. He was responsible for the construction of three churches, built after his return from Otago with other Māori Prisoners in 1872. 'Tutahi', which stands on the site of Titokowaru's Tauranga Ika Pa on the Nukumaru Straight near Pakaraka Road, was built in 1883. 'Te Ao Tawhi' was built in 1886 at Te Takerei-o-Aotea on Taumaha Road, Manutahi, while 'Te Kapenga', at Hukatere, Whenuakura, was completed in 1889, the year after Taurua's death. When Hukatere Marae was abandoned after 1894, it was relocated in 1911 to its new location at Pariroa Pa, Kakaramea, it has since been demolished. Ngawaka had shares in the Patea Shipping Company, and would be rowed into town in a majestic Waka for meetings. His wish for a permanent memorial to Turi and the Aotea canoe was not accomplished until 1933. Ngawaka Taurua was thought to be in his 70s when he died on Saturday 28 April 1888. He was buried on 7 May at Hukatere before a large gathering of Māori and Pakeha.

Tutange Waionui was a skilled warrior in his early days, fighting along side Riwha Titokowaru in the Land Wars. It is claimed that he is the one who shot and tomahawked Major Von Tempsky at Te Ngutu-o-te-manu. Tutange was in his mid teens at the time, 'strong and athletic, full of fire and courage'. A blue blood of Taranaki, tracing a direct descent through a line of high chiefs from Turi. His father, the old warrior Maruera Whakarewataua had trained Tutange in the use of the Taiaha and shaped him into a fearless warrior. Tutange won the distinction of a toa (brave), and on several occasions carried through some daring exploits. At Whakamara he rode into an ambush of 25 Forest Rangers, stood up in his stirrups, fired three pistol shots at the soldiers, and then rode away to join his people, who had made good their escape through the Pukemoko Gorge. In 1869 Tutange was one of the 74 Pakakohi men taken to Otago as 'Maori Rebel Prisoner's' until 1872. Upon his return home, Tutange spend years lobbying the Govenment for the Crown to give approval to move back to his ancestral lands around Kakaramea. Otoia had been his birthplace, but Pariroa Pa was given to his tribe in the early 1890's. He was far above average abilty as a warrior, and was a ready and effective speaker, he was not one to back down.

Pariroa Pa was established on Wilson Road at Kakaramea in 1894 by Tutange Waionui & his wife Ngaati, when they decided to move to the other side of the Patea River from Hukatere Marae at Whenuakura, after tapu was placed on that Pa when a man murdered his wife there. The sacred Makaka Stream runs past Pariroa Pa. Their fishing area on the Patea River - 'Te Arakirikiri' is near to Pariroa Pa.

Tutange was imortalized in various ways; the Patea Mail on 4 Dec 1935 tells the story from Mr A Howitt of Patea, after seeing the life size portrait of the legandary leader; 'All first saloon passengers journeying from Wellington to Lyttelton by the passenger Ship Rangatira, when descending to their cabins, are confronted at the top of the main, companionway by a magnificent painting of a life-size Maori warrior which adorns the wall...the artist has taken Tutange Waionui as his model, for it is undoubtedly a speaking likeness of Tutange. The only difference being that Tutange was not tattooed, but the artistic license has simply added the touch required to complete the old-time Patea Rangatira without in any way diminishing the likeness...In the hands of the artist J. McDonald and the historian James Cowan the stigma of the gaol and the defeatism complex of the imprisoned chieftain falls from him. In its place the nobility of his long line of rangatira ancestors reasserts itself." Tutange was also the model for crouching warrior with taiaha used on the New Zealand one shilling, later 10c coin. and he is well documented and photographed in James Cowan's 1911 book 'The Adventures of Kimble Bent'. Tutange was 66 years old when he died in January 1915, he is buried at Pariroa.

In 2009 Pariroa Pa celebrated 115 years since Tutange and Ngaati Waionui established and built up this tranquil settlement. Prime Minister John Key and Maori Party co-leader Tariana Turia were among the 600 guests at the Marae on Friday 6 October 2009. A framed copy of one of the many letters from Tutange to the Governor General requesting lands be returned for the Marae to be built at Kakaramea, was presented to the current leaders at Pariroa Pa that day.

The Aotea Memorial Canoe

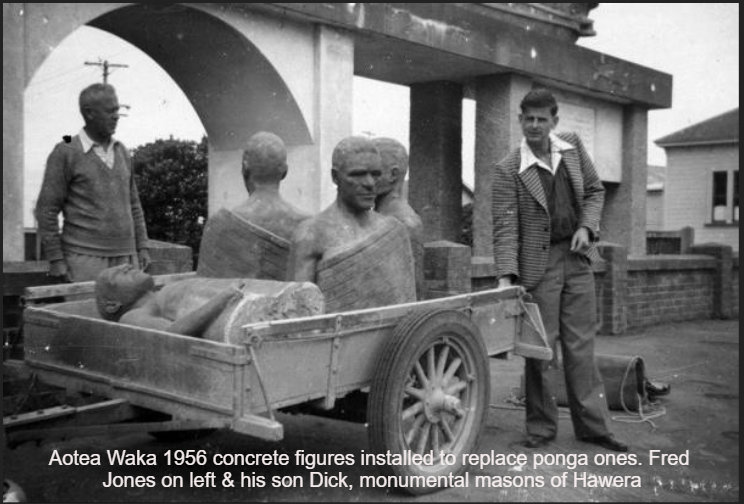

In the early 1930’s discussion arose amongst the Ngati Ruanui tribe about the building of a memorial for the tribes of the Aotea canoe. "He [Rev T G Hammond] had continually urged them not to forget the wish of Ngawaka Taurua that a memorial be erected to Turi. The Taranaki Maori Trust Board took up the idea....under the chairmanship of Tupito Maruera. The Borough Council was approached ...and with their agreement the site in front of the Town Hall was chosen. ...Mr F A Jones of Hawera suggested building it [the memorial] in concrete.... Towards the end, finance ran out and only four figures were in the canoe when it was unveiled August 1933.." (Patea: A Centennial History, 1981) Several additonal figures, carved from ponga trunks, were added later but replaced with five more concrete ones in 1956.

Henare Hikuroa built the concrete base and canoe structure which now now stands and the figures. Local Maori raised funds from local marae's and from other donations. The concrete pillars and base were rebuilt in 1990.

Information for this article from: A Centennial History of Patea 1981, Whenuakura 125yrs by Jim & Donna Baker

Only from a plane are there still discernible, to a keen-eyed airman, traces of that great highway of Maoridom, the Whakaahu-rangi Track, on which many of the great figures of history came and went in the centuries before the pakeha. The track, paralleling, fairly closely the present road between Lepperton and Patea, was part of the line of communication between Kawhia and Wellington. It avoided the country of the Taranaki tribes and was the means of uniting, by marriage, the leading families of the tribes descended from the people of the Aotea and Tainui canoes at Patea and Kawhia respectively. The trail was the major route from north to South Taranaki for many hundreds of years. The name is derived from a journey made by a Maori woman; Ruaputahanga, as she made her way back to her people in south Taranaki from Kawhia. Near present Stratford she slept looking up at the sky and the trail received it's name - Whakaahu-rangi or "turned towards the sky."

Ruaputahanga, the maiden of Lake Potakataka

The romance of this union lies in the story of Ruaputahanga, a maiden of renowned beauty, daughter of Keru, 7th generation in direct line from Turi, who lived at Paranui Village, east of Patea, and whose fame had reached the ears of Turongo, son of Tawhao chief of Kawhia. Turongo came to Patea but his wooing of the Aotea girl met with little success. Rua was in the habit of bathing in a lake called Potakataka, between Patea and Whenukura near the sea, and here Turongo went, hiding in the scrub by the water‘s edge, until Rua came to bathe.

He watched her disrobe and enter the water and then slipped up and picked up her clothes. Rua, endeavouring to hide herself in the water, asked Turongo what he wanted. His reply was that she should be his wife.

Rua could see no way out of the compromising situation and agreed. The story goes that she said: “It is well. Return to your home and your people, and in due time I and my people will come. Indeed, you have seen me in all my nakedness and I must perforce become your wife." So Rua went to Kawhia — but did not marry Turongo. It was in the end Turongo’s half-brother Whatihua who, captivated by her beauty, persuaded her to break her promise to Turongo and to become his (Whatihua’s) second wife. Turongo eventually married Mahinarangi, descendant of Kupe, the navigator and Paikea, captain of the Horouta canoe and from them sprang a line of illustrious chieftains beginning with their son Raukawa and ending with the five kings of Waikato, Potatau, Tawhiao, Mahuta, Te Rata and King Koroki

Rua bore Whatihua two sons but her husband’s first wife did not agree and eventually she left Kawhia, although Whatihua pursued her down the coast, beseeching her to stay. At length, weary of body and sick of heart, she arrived at at Mokau, where she stayed for some time, later becoming the wife of Mokau, the man after whom the river is named. For some reason not recorded except that she tired of Mokau, she left Mokau, and turned for her old home in South Taranaki, taking an old war trail which led to the east of Mount Taranaki. At a place near where Stratford is built she camped for the night. In going to sleep she lay on her back with her face up to the clear sky, and hence the name of that place and the track itself Whakaahurangi (Whaka-ahu to turn upwards; rangi, the heavens). Rua eventually reached her own people, one version saying she died at Orangituapeka Pa near Manaia. All versions agree, however, that she married again this time to Porou.

Waitore

Very close to Ruaputahanga's bathing pond; Potakataka on the Whenuakura coast is another significant site called Waitore. Over the years significant wooden artifacts from canoes have been found in this swamp area, they are currently in Aotea Utanganui and Puke Ariki Museum's.

Rangitawhi

At the mouth of the Patea River on the eastern side was Rangitawhi, the Pa built by Turi and his followers when they arrive in Patea in the 1300's. No trace of it can now be seen, as it has all eroded away with sand drifts. A substantial wharenui called 'Paeahua' was a feature at Rangitawhi. In his book 'The Story of Aotea', Rev TG Hammond tells of the remains of the Tuahu/Altar named 'Ranitaka' still on the landscape in the early 1900's... 'large slab-like stones from the bank of the river'. The village built nearby was called Kurawhao and was situated near the old Patea Railway station. Their cultivation's were on the site of the Harbour Masters house on the hilltop above and was called Hekehekeipapa. The stream 'Pararakiteuru' runs out of a spring above the railway cutting into the swamp below.

Tihoi

Tihoi was a fortified Pa on the Cliff overlooking the Whenuakura River mouth from the Patea side. It is thought it was built by Keru; a grandson or great grandson of Turi. When EJ Wakefield walked through in 1840 he described it as having a double row of palisading with the space between filled with earth, leaving small holes level with the ground through which muskets could be fired from a trench behind. It seems probable that Te Rauparaha modified the Pa for musket warfare in about 1823, when he spent some time there training his men for his expedition to the South Island. Te Oho, adjacent to Tihoi, was a fishing village associated with the Pa. The Papakainga associated with the Pa was called Paranui, situated near Baker's woolshed on Rakaupiko Road.

Haere Hau Pa

Haere Hau Pa was a fortified cliff top Pa on the south side of the Patea River, upriver a few hundred metres from the sea walls. EJ Wakefield also stayed here when he walked through in 1840. It was near the site of Wai-o-turi Marae. Haere Hau urupa overlooks the town of Patea, on the cliff top behind Wai o turi.

There was also a papakainga on the site of the town oxidization ponds between the Bridge and the River mouth. This area was later the site of the first European settlement in the 1860's, before the town moved up to its current site.

Wai-o-turi Pa

Wai-o-turi is on the south side of the Patea River, near the site of Haere Hau Pa. During the land Wars of the 1860's the area was part of the mass land confiscations by the Government. Upon his return from imprisonment in Dunedin with Māori Prisoners, in 1872, Chief Ngawaka Taurua fought long and hard to have this sacred place returned to his people. In 1876 Wai-o-turi was allocated back to Taurua and his people and was legally dated on the Crown Map in 1882 in his name. But it wasn't until 1933 that a new meeting house 'Ko Matangirei' and other buildings were built, and a large settlement established.

Kakaramea Redoubt

The Colonial Kakaramea (or Cameron) Redoubt on Wilson Road, was built on an existing fortified Pa, probably called 'Kakaramea Pa'. Further south near McKenna Rd was a kainga called Te Awhi. These were destroyed after the battle of Te Ngaio on 13 March 1865. Private James Nixon was the only european soldier killed in the battle, he was buried at the Kakaramea Redoubt, then re-interred on the hill at Scotland Street cemetery, Patea. The 50-80 Maori killed in the battle may also be buried in the vicinity.

Battle of Te Ngaio

Te Ngaio is the area of land between Whitehead Lane, Patea and the village of Kakaramea.

General Cameron had marched in his deliberate way up the coast and had established posts at several places as far as the Waingongoro River. The principal opposition he encountered was at Te Ngaio, in the open country between Patea and Kakaramea. The General, with about a thousand men of all arms, moved out from Patea camp on the 13th March for the Waingongoro. At about two miles from Patea volleys were fired into the column by a body of Māori’s posted under cover of a ridge parallel to the line of march, on the right, near the Patea River. The advance-guard was thrown out in skirmishing order, bringing round the left flank to attack the natives. The Hauhaus fell back in good order towards Kakaramea, fighting well in the open, with deliberation and bravery. There were about two hundred natives in action, and for all their inadequate numbers and inferior arms they opposed a manful front to the invading army. Retiring along the swampy ground toward Kakaramea they made the most of their knowledge of the terrain and their native genius in skirmishing, but nearly half of them were shot down. Eighty natives were killed (also reported that it was nearer to 50). It was the heaviest blow in point of causualties that the Hauhau tribes suffered in the West Coast War.

Tu-Patea, of Taumaha, describing this engagement of Te Ngaio, which was fought over his own tribal lands, said:— “I followed my elders into action, armed with my tomahawk. Over two hundred of our people came out to fight in the open. There were five women among them, not armed, but urging the warriors on. One of them, Tutaki's wife, was killed. The principal chiefs were Patohe, my father Hau-Matao, Te Waka-taparuru Paraone Tutere, and Te Mahuki. Our prophet was the old man Huriwaka, from Otoia, on the Patea. His god was Rura. Huriwaka, before the fight began that morning, prophesied saying, ‘To-day's battle will be good; it will be a favourable fight for us.’ But we were beaten, and eighty of our people fell on the field of Te Ngaio.”

There were many instances of native heroism and daring. An eye-witness, Dr. Grace, surgeon in the force, wrote: “The dignified and martial bearing of the Māori touched the hearts of our soldiers.” In the field hospital afterwards General Cameron asked a badly wounded warrior, “Why did you resist our advance? Could you not see we were in overwhelming force?” The Māori replied, “What would you have us do? This is our village; these are our plantations. Men are not fit to live if they are not brave enough to defend their own homes.”*

The tribes engaged in the fighting at Te Ngaio were chiefly Ngati-Hine, Pakakohi, and Ngati-Ruanui. It was the final attempt in strength to dispute the right of way with General Cameron. “The soldiers,” wrote Dr. Morgan S Grace in his “Sketch of the New Zealand War,” “no longer desired to kill the Māori, and disliked more than ever being killed by him.” He heard the sympathetic Irish soldiers say, after the exhibition of native bravery at Kakaramea (Te Ngaio):

“Begorra, it's a murder to shoot them. Sure they are our own people, with their potatoes and fish, and children. Who knows but they are Irishmen, with faces a little darkened by the sun, who escaped during the persecutions of Cromwell!”

Dr. Grace was in error, however, in a statement that very few of the Māori’s were killed in this battle in the flax and toetoe. The report of Colonel T.R. Mould, R.E., giving twenty-three as the number killed and mortally wounded, was equally astray. Wells's “History of Taranaki” makes the loss thirty-three killed, left on the field. A list of casualties in Gudgeon's work gives the killed at fifty-six—also under the mark. It was natural that the Maori losses should have been underestimated in the official reports of this and other engagements, as most of the dead were usually carried off the field. It is clear now from the narratives given me by Tu-Patea and other natives that the Hauhaus lost eighty killed at Te Ngaio, besides having many wounded.

A veteran transport bullock-driver who witnessed the encounter at Te Ngaio says: “After the battle I saw the dead body of the biggest Maori I ever set eyes on—he must have been 7 feet high.”

British casualties were a private of the 57th Pte James Nixon, shot dead and three men wounded. That afternoon the British force encamped in the captured village of Kakaramea, where a redoubt for 150 men was at once commenced. The position was about six miles from the coast and close to the Patea River; the present Township of Kakaramea is more inland and on higher ground.

On the following day the column moved on and camped at the Maori village Manutahi, three miles from the historic village of Manawapou, on the sea-coast. Detachments were sent to Manawapou, which was on the left bank of the Ingahape River, at the mouth; and, as it seemed practicable to beach boats on the sandy shore on the opposite side of the river, redoubts were constructed on the high ground to cover a depot of stores.

Otoia Pa

Pre 1869 the Otoia area of the Patea River was heavily populated by Te Pakakohi Maori. They had eel-weirs built across the River and abundant vegetable plantations on the riverflats. Owhio Gorge is the larger Gorge next to Otoia, and the Owhio Stream runs through it and into the Patea River. There were several different iwi living in neighbouring Papakainga/Village's - Whakapaiho Pa, Ruatuna Pa, Te Ngana Pa, Otoia Pa, Otautu Pa and Tupopou Pa.

Manutahi Pa

Also known as Te Takere o Aotea Marae on Taumaha Road was the prominant Marae in the area after Manawapou Pa was invaded and burnt by General Chute in the mid 1860's. Te Aotawhi Church was built on the Marae in 1886, one of three built after their men returned from imprisonment in Dunedin, the other two were at Hukatere Pa (Whenuakura) and Tauranga-ika (Nukumaru) known as Tutahi Church - a sacred stopping point still today. Te Aotawhi Church at Taumaha was dismantled at some stage and parts of it taken to Ratana to be used for a church there. The Church at Taumaha now is not the original.

Another papakaianga in the Manutahi area is Kaihuahua Pa, it was situation north of Manutahi, on the inland side of the main road, just before the Manawapou Hill.

The original Manutahi Pa was located on the hill top to the north of Taumaha Road where the rail way line intersects the road. It was a fortified native village within a circular stockade, which consisted of huge posts sunk in the ground and projecting upwards to a height of about 12 feet. In this enclosure were the whare and storehouses and a wharepuni named Parekau. Entrance to the pa was by the way of four separate gates, situated at points north, south, east and west of the stockade at each gate was quartered a certain tribe

The impressive Manawapou Pa was along the coastline overlooking the sea. This large fortified Maori village on the cliff top on the left bank of the Manawapou River had a commanding view of the area. Until the mid 1860's it was the home of a section of the Ngati-Ruanui, notable for the large stature of its men.

Turangarere is a sacred hill on the sea side of the main road at Ball Road intersection. It was a meeting place of early Maori, near the Mangaroa Stream. It is thought that the daughter of Chief Wharematangi is buried on top of the Hill.

Maori Land League hui ; early in 1854 at Manawapou

The formation of the Maori Land League, at a great hui of the West Coast tribes, at Manawapou, occured in the autumn of 1854 to discuss and oppose the sale of Taranaki lands to European settlers. Manawapou Pa was on the cliff top overlooking the sea, on the south side of the mouth of the Ingahape (Manawapou) River. An unusually large Wharenui was built for the gathering; it was 120 feet long and 35 feet wide. “Taiporohenui,” was the name given to it. This hui of the tribe agreed that no more land should be sold to the Europeans without the general consent of the federation, and that Maori disputes should not be submitted to European jurisdiction but should be settled by tribal runanga (councils). The idea of a Maori king for the Maori people was also discussed and fervently approved. Titokowaru was among those who signed the great oath, in his address to the crowd of over 1000 people he said…'the man first; the land afterward'. ….'My mother is dead but I was nourished by her milk. Let our land be kept by us as milk for our children'.

Kuranui Pa

Situated on an elevated, sharp bend in the Patea River between McColl's Bridge and the Dam. The Kuranui Stream runs into the Patea River nearby. Kuranui is another name for Moa and it is thought this was a Pa used for hunting Moa and not lived on in a permanent basis. It was the place that Ngawaka Taurua and his people sought refuge in from the Colonial forces in 1869. On the 13th June 1869 Ngawaka and other Te Pakakohi people were captured at this Pa. "In June Major Noake made a canoe expedition up the Patea, taking two hundred and seventy men in his flotilla, and captured the old chief Ngawaka Taurua and many of his Pakakohi Tribe. The warriors surrendered their arms, and were taken out to Patea. Gradually other sections of the tribe were rounded up on the Patea and the Whenuakura, until practically the whole of the fighting-men of the Pakakohi were captured, to the number of over a hundred, besides most of the women and children. The men, to their great disgust, were transported to Otago, and were not released until peace was thoroughly established on the West Coast. Had the Pakakohi anticipated this imprisonment it is extremely unlikely that they would have surrendered as they did". From: (THE NEW ZEALAND WARS: A HISTORY OF THE MAORI CAMPAIGNS AND THE PIONEERING PERIOD: VOLUME II: THE HAUHAU WARS, (1864–72)

The Aotea Waka Monument

Unique among all the memorials erected from one end of New Zealand to the other, a replica of the famous Aotea, or Aotearoa canoe, resting on its six great pillars that parallel the highway at Patea, is an arresting edifice, if not to local residents familiar with it, then most certainly to travellers with time to pause awhile and ponder the simple inscription: “This token of remembrance . . . by the descendants living throughout Aotearoa – of their ancestors Turi and Rongorongo, their family and fellow voyagers." And so the legend of Turi’s coming has to be re-told, as retold it must be to the end of time, for here is a treasured piece of the very history of the place, called Patea, these past six centuries or more. One of the most skilled of the many brilliant navigators who stud Maori folk-lore, Turi abandoned the sea at the end of his greatest voyage in the 14th century migration from Raiatea, one of the Cook Island group, earlier known as Hawaiiki, and walked in search of a “river that flows towards the setting sun.” He came upon Patea, for there the land that Turi smelled — “Te Whenui i hongia e Turi” – was sweet, as he had been told by the explorer, Kupe. “Ka patea tatoru,” which appears as an inscription on the mayoral chain presented to the Borough last year by the family of the late Mr F. Ramsbottom, a former mayor, were the words with which Turi informed his followers that they could lay down their burdens, having reached journey’s end.

Ten figures are represented in the canoe — Turi, his wife Rongorongo and their infant son nestling in a cloak on his mother’s back, Turi’s son Turangaimua and brother Rewa and five other men. In all, 11 hapus were represented among the passengers. On the voyage from Raiatea, Turi’s Party called at the small island Rangahua, supposed to be in the Kermadec group, and there gathered seeds of the karaka.

The Aotea reached New Zealand, land of the long white cloud, about Christmas time and it is generally conceded that it landed near the East Cape “when the lovely pohutukawa was in bloom.” It was a wonderful sight for the men who had been tossed about on the high seas for so many weeks.

In their search for fertile land the wanderers in due course arrived at Waitemata, which had been described to Turi by Kupe. According to legend they hauled their canoe across the isthmus from Tamaki to Manakau and sailed down to the Aotea anchorage at Raglan, where they went ashore to continue their search on foot, a scout, Pungarehu, being sent on ahead of the main party. Turi named several places as they journeyed and, with few exceptions, many have persisted until the present day. Kawhia was the first reached and so named because the party had to journey round the harbour. They travelled on, past Marokopa, Mokau, Waitara, Mangati and Matakitaki to Ngamotu, “where the earth did not smell sweet.” Then to Tapuwae, Oakura, Kaupokonui (the head of Turi), Marae-Kura, Kapuni (the encampment of Turi), Waingongora (the place where Turi snored), Tangahoe, Ohingahape and Whitikau.

Turi gave Mount Taranaki its name. A tribe led by Taikehu was said to be in possession at Patea when Turi arrived and legend has it that the two agreed to settle together, their people intermarrying and become one tribe, their pa being sited on the south side of the river and defended by the natural formation and the headland Rangitawhi. A large meeting house Matangerei was erected in the pa with a whata or storehouse called Paeahua. A nearby spring was named Pararakiteuru and, to make provision for religious ceremonies, an altar was erected and named Rangitaka.

First Kumara Harvest

Chanting some of the old songs, the tribes broke up the soil with wooden spades and planted the few seed kumara they possessed. The actual planting was done by Turi’s wife, Rongorongo, who was skilled in such work and broke the soil very finely. She formed small mounds of the fine soil and planted a seed in each. The mara (cultivation) was named Hekehekeipapa (where the Harbour Masters house is now on Whenuakura side of the River) and the virgin soil was fertile an enormous quantity was harvested. The Karaka seed brought from the Kermadecs was planted on the north bank and evidence of the groves which grew persisted until comparatively recent years; seed from this named Papawhero being carried up and down the coast.

Some of Turi’s people later settled to the north of the river near a good spring at Otaraiti and between two good fishing grounds, Whitikau and Kaitangata.

Another name which persists among the people in the district, Tupatea, arose from an incident when a party, led by Turangaimua, departed for the south. The chieftainess. Taneroa, daughter of Turi, drew attention to the fact and uttered a bitter curse as they stood in the river. Hence Tupatea — standing in the Patea River. According to some authorities, Patea should have been spelt Pa-wa-tea, the pa with a clear outlook. Troubled circumstances, believed to be the death of Turi's son in battle with another tribe, added yet another chapter to the legend of Turi. He disappeared, some claim back to Hawaiiki, and his last resting place remains a mystery. But he left behind him descendants who were to become. a great race of people and who still have descendants living in the region

Raumano

The land behind the site of the Patea railway station is known as Raumano, or the place of a thousand leaves. It was said to have been a swamp producing flax, tutu, raupo and toe toe and was the home of pukeko, parera and Kotuku. An old chant sung by the Maoris of Hukatere told of a landslide in that locality, which carried away many people into the sea “and across to the West Coast.” Pariroa Pa, lying in a sheltered valley off Wilson Road at Kakaramea, replaced Huketere Pa on the eastern bank of the river when Huketere came under tapu. This area and nearby Otoia Pa nearer to Alton is the home of Te Pakakohi Tribe.

DIVISION OF PEOPLE INTO MAIN TRIBES

The people of the Aotea canoe, after their arrival in this country about the year 1350 A.D., made their first home at Patea. It was at Patea that trouble broke out which divided the people into the main tribes of Ngati Ruanui and Nga Rauru. It happened this way; Turi, the leader of the Aotea migration, had a number of children, among whom were a son, Turanga-i-mua, and a daughter, Tane-roroa. Tane-roroa mar-ried Uenga Puanake, a man of high rank of the Takitimu people. At the instigation of Tane-roroa, her husband killed some dogs belonging to Turanga-i-mua. These they cooked and ate. The story says that at that time Tane-roroa was expecting a child and craved for the flesh of dogs. Turanga-i-mua soon found out about this and the thieves were exposed. Thus Tane-roroa and her husband could no longer remain in the old home so they crossed the river and settled to the north at a place called Whitikau. This is three miles down the coast from the mouth of the river toward Kakaramea.

Founder of Tribe

Whitikau became, in later Years, a famous place in the story of South Taranaki for it was here that Tane-roroa's child Ruanui was born, he who founded the tribe that even today carries his name. Ngati Ruanui’s lands of old stretched from the northern bank of the Patea River almost to Oeo and inland to the slopes of Mount Taranaki. At Whitikau there was a famous place of learning called Kaikapo and it was in Kaikapo that a quarrel broke out which was followed by a further division of the people. Some of Tane-roroa’s tribe left Taranaki after this quarrel and went, it is believed, to Wairarapa. South of the river the people of Turanga-i-mua spread over the country- side, building villages and fortifications, mainly in the coastal strip but also inland in some places. The tribe took the name of Nga Rauru after an ancestor.

Turanga-i-mua was a great warrior and led expeditions to other parts of the country, meeting in battle those members of the earlier migrations who could gather war parties to oppose him. Maori history — that is the stories handed down by the descendants of the last migration — is full of stories of how the original inhabitants fled before the powerful new comers.

Counter attack

However, they must not all have been as ‘unwarlike’ as the stories say because after one battle in which Turanga-i-mua had gained a notable victory, the survivors came back with a counter-attack in which Turanga-i-mua and a number of his leading warriors lost their lives.

The battle took place in the Ruahine Ranges. Turanga-i-mua’s body was brought back to Patea by the survivors and there his aged father Turi mourned for his warrior son and could not be comforted. Turi then disappeared and the story is that his spirit fled from the new home to the old and found peace at last in the islands from which he had set out long years before as the leader of the great adventure. Turi must have been saddened too by the enmity which had arisen between his children. The quarrel which had broken out be-tween Tane-roroa and Turanga-i-mua was not allowed to die down. Over the centuries it simmered, now and again breaking out into open warfare.

Great Leaders of the 1800's

Riwha Titokowaru was undoubtedly one of the most strategic warrior of Land Wars. Despite being heavily outnumbered Tītokowaru won several stunning victories. He was both an extremely talented military engineer and a master of tactics. By early 1869 he had won back 110 km of territory between the Waingongoro and Whanganui rivers. His force grew from 150 to around 1000, and he gained the tacit support of the King Movement. His victories almost brought the colony to its knees, and the government considered returning confiscated land. But at the height of his success Tītokowaru’s army mysteriously fell apart. As Belich remarks, Tītokowaru lost his war but the government can hardly be said to have won it. The government left Tītokowaru alone, and he became a strong supporter of the pacifist prophets Te Whiti and Tohu at Parihaka. When creeping confiscation began again in 1878, he helped to organise a campaign of non-violent resistance.

Ngawaka Taurua was the tribal leader of Pakakohi, based a Hukatere Pa. He was responsible for the construction of three churches, built after his return from Otago with other Māori Prisoners in 1872. 'Tutahi', which stands on the site of Titokowaru's Tauranga Ika Pa on the Nukumaru Straight near Pakaraka Road, was built in 1883. 'Te Ao Tawhi' was built in 1886 at Te Takerei-o-Aotea on Taumaha Road, Manutahi, while 'Te Kapenga', at Hukatere, Whenuakura, was completed in 1889, the year after Taurua's death. When Hukatere Marae was abandoned after 1894, it was relocated in 1911 to its new location at Pariroa Pa, Kakaramea, it has since been demolished. Ngawaka had shares in the Patea Shipping Company, and would be rowed into town in a majestic Waka for meetings. His wish for a permanent memorial to Turi and the Aotea canoe was not accomplished until 1933. Ngawaka Taurua was thought to be in his 70s when he died on Saturday 28 April 1888. He was buried on 7 May at Hukatere before a large gathering of Māori and Pakeha.

Tutange Waionui was a skilled warrior in his early days, fighting along side Riwha Titokowaru in the Land Wars. It is claimed that he is the one who shot and tomahawked Major Von Tempsky at Te Ngutu-o-te-manu. Tutange was in his mid teens at the time, 'strong and athletic, full of fire and courage'. A blue blood of Taranaki, tracing a direct descent through a line of high chiefs from Turi. His father, the old warrior Maruera Whakarewataua had trained Tutange in the use of the Taiaha and shaped him into a fearless warrior. Tutange won the distinction of a toa (brave), and on several occasions carried through some daring exploits. At Whakamara he rode into an ambush of 25 Forest Rangers, stood up in his stirrups, fired three pistol shots at the soldiers, and then rode away to join his people, who had made good their escape through the Pukemoko Gorge. In 1869 Tutange was one of the 74 Pakakohi men taken to Otago as 'Maori Rebel Prisoner's' until 1872. Upon his return home, Tutange spend years lobbying the Govenment for the Crown to give approval to move back to his ancestral lands around Kakaramea. Otoia had been his birthplace, but Pariroa Pa was given to his tribe in the early 1890's. He was far above average abilty as a warrior, and was a ready and effective speaker, he was not one to back down.

Pariroa Pa was established on Wilson Road at Kakaramea in 1894 by Tutange Waionui & his wife Ngaati, when they decided to move to the other side of the Patea River from Hukatere Marae at Whenuakura, after tapu was placed on that Pa when a man murdered his wife there. The sacred Makaka Stream runs past Pariroa Pa. Their fishing area on the Patea River - 'Te Arakirikiri' is near to Pariroa Pa.

Tutange was imortalized in various ways; the Patea Mail on 4 Dec 1935 tells the story from Mr A Howitt of Patea, after seeing the life size portrait of the legandary leader; 'All first saloon passengers journeying from Wellington to Lyttelton by the passenger Ship Rangatira, when descending to their cabins, are confronted at the top of the main, companionway by a magnificent painting of a life-size Maori warrior which adorns the wall...the artist has taken Tutange Waionui as his model, for it is undoubtedly a speaking likeness of Tutange. The only difference being that Tutange was not tattooed, but the artistic license has simply added the touch required to complete the old-time Patea Rangatira without in any way diminishing the likeness...In the hands of the artist J. McDonald and the historian James Cowan the stigma of the gaol and the defeatism complex of the imprisoned chieftain falls from him. In its place the nobility of his long line of rangatira ancestors reasserts itself." Tutange was also the model for crouching warrior with taiaha used on the New Zealand one shilling, later 10c coin. and he is well documented and photographed in James Cowan's 1911 book 'The Adventures of Kimble Bent'. Tutange was 66 years old when he died in January 1915, he is buried at Pariroa.

In 2009 Pariroa Pa celebrated 115 years since Tutange and Ngaati Waionui established and built up this tranquil settlement. Prime Minister John Key and Maori Party co-leader Tariana Turia were among the 600 guests at the Marae on Friday 6 October 2009. A framed copy of one of the many letters from Tutange to the Governor General requesting lands be returned for the Marae to be built at Kakaramea, was presented to the current leaders at Pariroa Pa that day.

The Aotea Memorial Canoe

In the early 1930’s discussion arose amongst the Ngati Ruanui tribe about the building of a memorial for the tribes of the Aotea canoe. "He [Rev T G Hammond] had continually urged them not to forget the wish of Ngawaka Taurua that a memorial be erected to Turi. The Taranaki Maori Trust Board took up the idea....under the chairmanship of Tupito Maruera. The Borough Council was approached ...and with their agreement the site in front of the Town Hall was chosen. ...Mr F A Jones of Hawera suggested building it [the memorial] in concrete.... Towards the end, finance ran out and only four figures were in the canoe when it was unveiled August 1933.." (Patea: A Centennial History, 1981) Several additonal figures, carved from ponga trunks, were added later but replaced with five more concrete ones in 1956.

Henare Hikuroa built the concrete base and canoe structure which now now stands and the figures. Local Maori raised funds from local marae's and from other donations. The concrete pillars and base were rebuilt in 1990.

Information for this article from: A Centennial History of Patea 1981, Whenuakura 125yrs by Jim & Donna Baker